This year has seen a renewed focus on minimum wage issues with the 110th anniversary of the Harvester decisions, wage stagnation and the ACTU launching a living wage campaign. In this article, AIER Board member Keith Harvey takes us through the Harvester decision and its legacy.

The ACTU’s new campaign for a return to a ‘living wage’ for all Australian workers, not just a Minimum wage, reminds us of where this concept came from in the first instance.

In today’s society, most people work to live, not live to work, but are wages and salaries designed or sufficient to meet the costs of living?

This was also the key question considered by one of the earliest and best known of all workplace-related decisions in Australia’s industrial history — the Harvester decision.

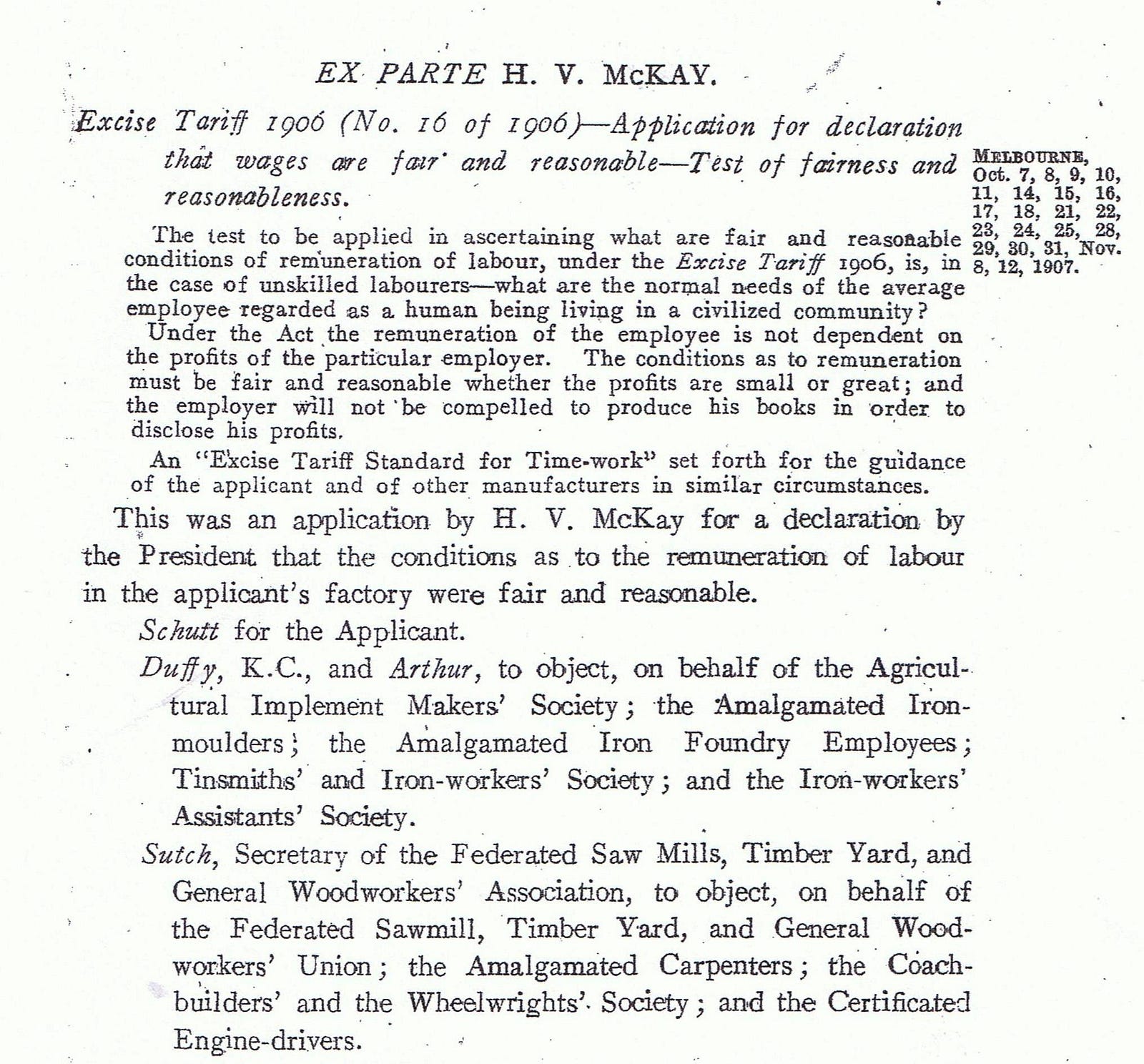

This decision was so called because it was made as a result of an application in 1907 by H V Mackay, the owner of the Sunshine Harvester factory in Melbourne’s west, seeking a declaration that the wages paid to the Company’s workers were ‘fair and reasonable’. The unions representing the workforce opposed the Company’s application.

The Sunshine Harvester factory manufactured agricultural implements including the famous Sunshine brand combine harvester after which the factory [and later the suburb] was named.[i] In the early days of Federation, tariffs were the major source of federal government revenue and imported as well as locally made goods were subject to tariffs.

Under the Excise Tariff Act 1906 an exemption from the tariff could be obtained for local products if the business could show that it was paying its workers ‘fair and reasonable’ wages. Mackay’s application for a declaration to that effect came before one of Australia’s best known judges of the Arbitration Court, Justice H B Higgins, although the case was not, strictly speaking, a labour Arbitration case.

Justice Higgins was concerned that the Excise Tariff Act provided little or no guidance as to what ‘fair and reasonable’ meant in the context of wages. He concluded that it encompassed two different things — fair in respect of process and reasonable as to amount:

“I cannot think that an employer and a workman contract on an equal footing, or make a ‘‘fair ” agreement as to wages, when the workman submits to work for a low wage to avoid starvation or pauperism (or something like it) for himself and his family; or that the agreement is “reasonable” if it does not carry a wage sufficient to ensure the food, shelter, clothing, frugal comfort, provision for evil days & etc. as well as reward for the special skill of an artisan if he is one”. [ii]

Ex parte H.V. McKay (Harvester Case), (1907) 2 CAR 1

Implicit in the decision of Justice Higgins was the idea that an agreement between and employer and an employee could only be fair if bargaining power was relatively equal and that the outcome was not an ‘unequal treaty’ imposed on the workers because their only alternative was poverty. The State might have to intervene to ensure fair treatment.

Equally, it can be seen that Justice Higgins wanted to be sure that unskilled workers — the lowest on the wage scales — could survive and provide for their families at least to a level of ‘frugal comfort’ on their wages. If businesses could not provide such wages, they should not be in business.

In other words, Higgins did not believe that wage setting could be left only to the ‘higgling of the market’, as he put it, quoting 18th century economist Adam Smith. Both these messages still have meaning 110 years later and are an important Australian contribution to the means of wage fixation which do not exist in many other countries which seem to be content to leave these matters to the market.

To arrive at what was a reasonable living wage for unskilled labourers, Higgins examined the family budgets of a number of workers. These budgets were provided by the wives of a number of skilled workers — presumably the men were not in a position to say what it cost to run a household!

Sunshine Harvester labourers were paid six shillings a day at the time the application was made. After considering the family budgets, Higgins decided that this was not enough to support a man, his wife and three children in ‘frugal comfort’ and therefore declared that the wages paid by the factory were not fair and reasonable.

Higgins went on to declare seven shillings a day [42 shillings a week for the six day week then worked] as a fair and reasonable wage for unskilled labourers and additional amounts for more highly skilled workers such as tradesmen, the highest paid of whom — pattern-makers — were to get 11 shillings a day.

Most of the Harvester decision is spent considering the rates of pay which should be fixed for the pay of tradesmen — in doing so, Higgins used a variety of techniques including comparable worth or value and comparative wage justice. These methods have also had an enduring place in wage fixing in Australia.

The floor for wages subsequently became known as the ‘Basic Wage’ with additional ‘Margins’ for skilled workers, later combined into a Total Wage. Today they are called Minimum [Award] Wages and are reviewed each year by the Fair Work Commission in the Minimum Wage case. The Minimum wage case was until very recently still known as the “living wage” case, a legacy of the Harvester decision concepts. As well as minimum award wages for all classifications, the Commission sets a minimum federal wage rate below which no federal system employee can be paid.

Justice Higgins set a number of other employment standards as well in this 1907 decision, in relation to overtime and public holiday rates of pay:

“Part I X .-Overtime —

At the rate of time and a quarter for two hours, time and a half for the next two hours, and double time afterwards.Double time on Sundays and Christmas Day, New Year’s Day, Good Friday, and Eight Hours Day.” [iii]

Ironically, the decision of Justice Higgins in the Harvester case was short-lived. Mackay appealed the decision and the very Act under which it was made was struck down the High Court as unconstitutional — as well as the decision itself.

However, the Arbitration Court itself picked up the logic and the substance of the Harvester decision and began applying it in federal awards from 1908. The key aspect of the Harvester decision was that a ‘civilised community’ should ensure that its workers could, by their labour, support themselves and the needs of their families in some sort of comfort.

But what about the rates of pay for women?

All the rates of pay set by Justice Higgins in the Harvester decision were for classifications in which only men worked. The logic of the decision, that those ‘reasonable’ rates of pay should allow a man to provide for himself, his wife and children, immediately raised another vital question: what rates should women be paid?

At the time, women were not considered to have the responsibility of providing for a family, although of course in practice many actually did so. It was also a time when social security was very limited or non-existent and thus single women with children to support were doubly disadvantaged.

The fact that many single men did not have families to support did not seem to disturb decision makers at the time. They were paid the same “needs based” rate of pay as married men irrespective of the absence of any ‘breadwinner’ role, while women with such responsibilities were not. This was highly discriminatory and harsh.

In some early arbitration decisions, women who were doing the same work as men were awarded equal pay — for example in the Fruit Pickers case of 1912. Justice Higgins decided that male and female fruit pickers were to be paid the same rate, but that fruit packers — who were all women — were paid only 75% of the pickers’ rate.

However, most women were paid even less. For the most of the first half of the 20th century women were paid just 54% of the male rate in most industries and occupations, except where they worked in precisely the same occupations as men [and even then, not always].

This general female rate was raised to 75% of male rates during World War 2 as women entered the workforce in larger numbers to replace men in the armed forces, but it was not until the early to mid-1970s that unions were able to successfully convince arbitration tribunals that equal award rates should apply to both men and women workers.

Today, equal minimum rates of pay apply to both males and females under all awards and collective agreements. In the process, it has become more difficult to determine precisely the ‘needs’ base of the minimum wage — in effect it is a ‘unit’ minimum wage based on the needs of an individual worker irrespective of social, household or family status and responsibilities. It can hardly be otherwise in today’s society.

Today, social security is a responsibility of the State and the needs of families are at least in part addressed by measures such as family tax benefits. Rates of pay do not need to take so much account of the existence of ‘evil days’ as Justice Higgins described them; that is, presumably, periods of unemployment and sickness.

However, the struggle for equal pay for women workers is not over. For a variety of reasons, including continuing gender segmentation of the workforce, the average earnings of women are still stubbornly below those of male employees.

The Fair Work Act contains provisions allowing unions to apply to increase rates of pay to ensure that work of comparable worth is equally rewarded. This is what the ASU and a number of unions in the social, community and disability services sectors of the economy did some years ago in a landmark decision still being implemented. [iv]

While the Harvester notion of the needs of a worker is now well outdated, the principle established by Justice Higgins that the living needs of workers must be a principal and basic element of wage fixation remains, although it has yet to be fully realised.

Further reading and online resources

In 2011, Fair Work Australia, as it was then known, published a book on the Harvester Decision and other key industrial decisions including equal pay for women, aboriginal workers and young people: Waltzing Matilda and the Sunshine Harvester factory — the early history of the Arbitration Court, the Australian minimum wage, working hours and paid leave, Fair Work Australia, 2011.

The Fair Work Commission has a webpage devoted to the Harvester case where you can download and read the full decision and the transcript of the hearing: https://www.fwc.gov.au/waltzing-matilda-and-the-sunshine-harvester-factory/historical-material/harvester-case

The Fruit Pickers decision is here: https://www.fwc.gov.au/sir-richard-kirby-archives/cases/case?title=1912%20Fruit-pickers%20Case

The second equal Pay case decision [1972] is here: https://www.fwc.gov.au/sir-richard-kirby-archives/cases/case?title=1972%20Equal%20Pay%20Case

Documents relating to the Social, Community and Disability Services Equal Remuneration case 2010–12 can be found here: https://www.fwc.gov.au/cases-decisions-and-orders/major-cases/equal-remuneration-case-2010-12

References

[i] The site of the factory is now a shopping centre.

[ii] [1907] 1 Commonwealth Arbitration Reports 2 at page 4

[iii] Ibid, at page 21

[iv] https://www.fwc.gov.au/cases-decisions-and-orders/major-cases/equal-remuneration-case-2010-12